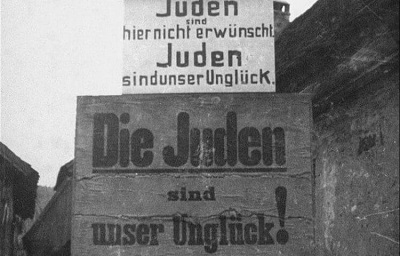

Antisemitism is our misfortune

The wonderful Bari Weiss has attempted once again to understand why the world hates Jews. She starts with a song by Tom Lehrer, “National Brotherhood Week”, from the 1960s (but popular in her family when she was a child) and says that the lyrics do not sound like a funny punchline of a satirical song now, but like a diagnosis of social attitudes in the 21st century.

Two years ago Bari Weiss wrote a book, How to Fight Antisemitism, and she says that in these two years much has changed. For a long time, and for the first time in history, Jews in America didn’t feel discriminated against. Weiss believes that the American-Jewish holiday ended on 27 October 2018 when a gunman opened fire on people gathered for prayers in a synagogue in Pittsburgh. As she writes, it was the day American antisemitism moved “from antisemitism of horse-and-buggy velocity to something more like a bullet train”.

Hatred is now everywhere, antisemitic statements are accepted in Congress, political salons, editorial offices and universities, physical assaults are nothing out of the ordinary. This is very bad news not only for American Jews but also for America.

Bari Weiss is an American Jew, I am a European Gentile so, although we share a system of values, we see this phenomenon from different perspectives. Weiss quotes an article by Dora Horm:

“ Since ancient times, in every place they have ever lived, Jews have represented the frightening prospect of freedom. As long as Jews existed in any society, there was evidence that it in fact wasn’t necessary to believe what everyone else believed, that those who disagreed with their neighbors could survive and even flourish against all odds.”

Bari Weis writes then that where there is freedom, where diversity is valued, Jews are tolerated. Freedom of thought, religion, and expression is protected. However, where these freedoms are seen as a threat, also Jews are seen as a threat. And this is no new phenomenon.

The Left believes that it’s fighting for equality and justice, that it’s better when everybody is worse off than when some have it better than others. (For half a century now I have presented this ideology differently – it’s better to be without bread than to see daily how the baker is getting richer.)

This exalted need for equality and justice leads to an equally strong need to demonize Jews. For them, writes Weiss:

„Zionism is is nothing but settler-colonialism; government officials justify the murder of innocent Jews in Jersey City; Jewish businesses can be looted because Jews “are the face of capital.” Jews are flattened into “white people”, our history obliterated, so that someone can suggest with a straight face, that the Holocaust was merely “white on white crime” or that Anne Frank was a colonizer.”

The argument for a correlation between freedom of religion and expression and the blossoming of Jewish communities in a given society is to some degree supported by historical facts. There are also those who claim that there is another correlation between economic progress and tolerance and acceptance of a Jewish minority, which leads to the question of why a rise in pressures for religious or ideological conformism almost always leads to a rapid rise of antisemitism.

We can blame tradition. After all, it’s known the even before the exile from Israel (some will insist that Romans exiled Jews from Palestine) Jews took thirty pieces of silver for turning Jesus-Palestinian in to Roman soldiers, and on top of that instead of distributing the money among the poor they invested it in a bakery. (By the way, the idea of distributing money instead of investing it, even if not fully Jewish, was popularized by Jews even before Palestinians invented Christianity. I definitely dislike this idea, so, please, don’t say that I’m never critical of Jews.)

However, I suspect that the attractiveness of antisemitism is not exclusively connected with the Christian tradition and the convenience of reaching for this very well established epitome of Super-Other. Antisemitism is the eternal dream of a chained watchdog of biting a postman to death.

I remember a sentence I read somewhere that “a translator is a postman between civilizations” (I associate it with Pushkin but Google doesn’t support me.) There were many peoples exiled from their native turf. Their remnants dissolved in other cultures and what’s left are vestiges which are difficult to identify. Why do Jews – dispersed all over the world – retain their religion and their liturgical language; why didn’t their remnants dissolve in other nations? Was it the power of religion or rather the effect of rejection? What was the main reason for this rejection? Could it be ancient geopolitics?

Israel was a corridor between the Nile valley and the civilizations originating in the Fertile Crescent, where agriculture and the first towns arose. Jews were a source of slaves, but often also allies and brokers. They were drawing from Babylonian and Persian cultures, from Egyptian and later from Greek. Their religion shows how well they knew and made use of the cultures of their neighbors.

The strength of this religion depends, I think, on Jewish argumentativeness, their permanent quarrels with God, but also – or, maybe, first of all – their emulation of Egyptians in the universal education of boys, as well as trade that is constantly counting, weighing, and calculating. Poor soil without any chance of large-scale plantations and an economy based on slavery. Strong commerce and craft. Romans exiled a small nation of individualists in which the attachment to their God, to books, to calculating, and to eternal arguments dominated.

Jews were (and still are) postmen between civilizations. They were thrown out and they took with them a familiarity with other cultures, a knowledge of languages, and ties with other Jewish centers. They were the best candidate for a postman between civilizations. And this made them both attractive to rulers and a threat to guardians of a backwater. Antisemitism is the inborn hatred of a chained dog for a postman.

People kept on a chain of religion and tradition couldn’t stand otherness looking into their backyard. Many have described this essence of antisemitism, but perhaps it is best captured in Joanne Greenberg’s The King’s Persons, and for the Muslim world in Leo Uris’ The Haj.

The first book describes the pogrom of Jews in York in the twelfth century, the second describes the reactions of Palestinian Arabs to Jewish settlers in the twentieth century. Read in parallel they show perfectly the depth of despair that the appearance of a postman in the backyard causes a dog chained there. (Both in the twelfth and in the twentieth century the dog was unchained and set on the postman in order to save one’s own backwater from change, to get rid of debts, and to divert the dog’s attention away from the one who is starving him and beating him with a stick.)

It is interesting that only Muslim dissidents are now saying loudly and clearly that antisemitism is their misfortune, that progress depends on getting rid of this serious disease.

Translation: Małgorzata Koraszewska and Sarah Lawson